By Ward Batty

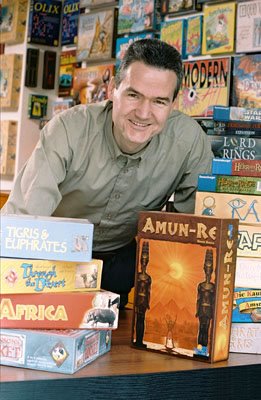

By Ward BattyReiner Knizia is probably the most prolific game designer of all time, with over 200 published games. The number of Knizia games that have been or are scheduled to be published this year alone is over forty. While some of these are re-releases of older, previously published games, for one designer to produce so many titles is quite a feat. Consider that most boardgame companies don't release forty games a year.

You don't achieve this sort of creative production without taking a systematic approach. Knizia rises at 4:30 each morning, a habit from his days when we was designing games in addition to working in banking. His early morning hours, during which he says he is his most creative, are spent exercising and thinking about his designs. His afternoons are spent in his office, dealing with publishers and other tasks, such as speaking with the press. Evenings are spent in play testing sessions with the number of groups around London, where he currently resides.

Knizia says that game design has been an interest of his since early childhood. "I have some games in the basement that I designed when I was six years old. Even so, in my early years, I never tried to publish any of these games. The excitement was in playing them. It seemed that I could never find, or be able to afford, enough new games in the shops and I didn't see the themes that interested me, so I would invent my own to play. I would also make a lot of games around Monopoly. We would play it sometimes, but I would also take the money from the game and improvise a new game around that. With many games, I would play it a few times, get an overview, and start experimenting with my own rules."

Unlike many designers who work on games with other designers, Knizia works alone. While he is the sole designer, Knizia works in conjunction with his many play test groups. By working with several groups of play testers he can draw on their collective experience. "I'm very sure it wouldn't work for me to collaborate with one specific other designer. When I'm very excited about a game I can become very obsessed about it and will spend a lot of time on it. With my play testers I get a lot of input from them and I owe them a lot. We have been together now for many years and they bring a lot of variety into the process."

Knowing Knizia's past as a mathematician and having played many of his games that feature number cards, often with one through six, I had concocted a theory of how Knizia was sharing his inherent love of numbers with the world through his games. Reality differs from my theory in this case as he tells me that most of his game designs begin with the theme. "The theme, mechanics and the materials in the game must work as one unit and if they don't gel together I think the game is not complete. Sometimes people say that my games are a bit abstract. I'm a more scientific man. My approach is that the game should have very simple rules and depth of play comes out of these simple and unified rules. There may be a lot of details, but usually I have a good thematic reason for these additions."

Does Reiner Knizia have an inherent love for the numbers 1-6? "I think that every designer has his own handwriting,? admits Knizia, "Maybe you discover things about me from playing my games that I don't know about myself. But I am a scientist and that influences my character and how I see the world. So maybe my games have more of the analytical side stressed, not because I am doing this in awareness but more because that's who I am and that's how my world looks like. But there is a second aspect to it. I believe that games and especially the rules should be simple. I don't, for example, think it is necessary to operate with big numbers. Why should players have to add up 47 plus 39? I'm trying to reduce the game points and many aspects of the game to very simple numbers and mechanics. If players fight over 4 or 5 points it is the same as if they fight over 400 or 500 points. Therefore I am reducing many of my systems to small numbers. The numbers 1-6 does not obsess me; it is just that when you reduce it to small numbers you will always end up with the numbers 1-6. I don't want to distract people with big numbers or the handling of the game components. I want to make the world very easy to the players so they can then concentrate on their game strategy."

Does Reiner Knizia have an inherent love for the numbers 1-6? "I think that every designer has his own handwriting,? admits Knizia, "Maybe you discover things about me from playing my games that I don't know about myself. But I am a scientist and that influences my character and how I see the world. So maybe my games have more of the analytical side stressed, not because I am doing this in awareness but more because that's who I am and that's how my world looks like. But there is a second aspect to it. I believe that games and especially the rules should be simple. I don't, for example, think it is necessary to operate with big numbers. Why should players have to add up 47 plus 39? I'm trying to reduce the game points and many aspects of the game to very simple numbers and mechanics. If players fight over 4 or 5 points it is the same as if they fight over 400 or 500 points. Therefore I am reducing many of my systems to small numbers. The numbers 1-6 does not obsess me; it is just that when you reduce it to small numbers you will always end up with the numbers 1-6. I don't want to distract people with big numbers or the handling of the game components. I want to make the world very easy to the players so they can then concentrate on their game strategy."Knizia's systematic approach also extends to the type of games he designs. These cover a wide range from Tigress & Euphrates, one of the most-respected "gamer's games" to children's games and even licensed tie-in. Knizia has designed games for such properties as the Lord of the Rings, Simpsons, Bibi Blocksberg, Star Wars, King Arthur and even Donald Duck. "When I decided to design games full-time eight years ago, I didn't want to dig deeper into the same type game all the time." Knizia says, "I wanted to spread out my interest. I want to work for different audiences, work with different game systems, and different themes even different possibilities like having electronics in the game. So I want to do children's games and two-player games and whatever else I can think of. Anything I haven't done yet is particularly exciting for me. I read Donald Duck comics as a child, so now to be doing a game with that character, I find that very thrilling. It took a while to be able to get access to these projects and now I enjoy having that access."

After creating mostly games for the adult and family market early in his career, over the last few years he has turned his interest to children's games. You can't just take a strategy game and make the strategy easier, Knizia says, "I think that would be the wrong approach to fascinate children. Children see the world with different eyes. They touch much more than we adults do. They want to experience the game with their fingers and hands and even put things in their mouth. So the experience and the components play a much bigger role. This fires up their imagination. You can't put a black and white abstract thing in front of them and say this is so-and-so, they just don't see that. So I think one needs to come from a more optical and tactile experience. The world of the game needs to be the kids' world, simple and lovely. The rules need to be very short and simple. You need to speak to the kids through their language, to their perception of the world."

Children's games have to be play tested with kids and this has its particular challenges, says Knizia. "One good thing is that the kids are not nice to you, they are simply honest. They don't even say anything, necessarily. You can tell by watching if they are fascinated with the game. Either they are concentrating on the game or they run off and do something else. You get very good feedback and very good insights. Since I've been playing with children, especially small children, I've learned a lot about the essence of playing. Of course they also have a great ability to destroy everything. My prototypes usually don't last very long when I'm playing them with kids (laughs). But that's part of the play testing as well because then we know what materials we can and can not use."

One can't get over 200 games published without an understanding of the commercial side of the business. Knizia explains there are two very different categories of game design. "One is the pre-game design where I come up with my own ideas and I'm not thinking of the finished product. The other is an up-front agreement to do a specific type of game and then I have to deliver that. The first kind is much more fun. I sit down and develop my own ideas and then I don't really have a target group in mind. I always say the game is like a child. You can lead and you can guide it, but eventually it develops by itself and it will have its own personality." During the development process, a game might start as a card or a board game and then would develop into a tile-laying game and then the theme would change. Many games that are published end up being very different from the genesis of the idea. "Why should I restrict myself by saying this has to be a certain way? It is best to let the game naturally develop into something that can create the most fun and excitement."

The other type is when there is an up-front agreement. "In these situations," explains Knizia; "I need a publisher and the agreement up front so we can acquire the license. Then there is also the understanding of what the target market is, how expensive the game will be, at what point in time will it come out and what sort of materials we can use. So there are many restrictions coming in and of course you also have a deadline. So it is less fun, more work and much more demanding. It's a much bigger challenge to do, but, of course, these are usually the big, very exciting projects which are certainly worth doing as well."

Knizia has been successful getting games published in both the US and Europe, but acknowledges that the markets are different. Says Knizia, "In America, the theme is seen as the game where as in the European the game mechanics and the game system are seen as the game." Knizia tells a story about when he took a game prototype to America. It had an Egyptian theme and when an American publisher saw the theme they said, "We are not interested in this game, we have a game about Egypt and we don't need another." So Egypt was the game to them. Knizia asked them "Won't you at least have a look at it?" and they said no, we don't want this game. A few weeks later he was back in Germany showed the same game to a German publisher. The publisher sees the game has an Egyptian theme and says "Oh, are just in preparation of an Egyptian-themed game, so the Egyptian theme wouldn't work for us. But let's see the game first and then we can see what we'll do about the theme." In Germany the game was not the theme, but the game system. So there is a very different perception of what is a "game." For Knizia, that understanding is the starting point for what games he offers to the different markets.

But even in the same market, publishers are very different. They have their own niches and look for their own products, but they also vary in how they produce the games and the criteria by which they choose what to publish. Once accepted, some will take the game as delivered and some want to add their own ideas. "Sometimes these ideas are good, and sometimes they are not so good." says Knizia, "Some publishers are much more pleasant to work with than other publishers. So you have a selection process where publishers are trying to choose the good games and I am trying to choose the good publishers."

Some Knizia games have more lives than Shirley McClain's cat. Quandary, Thor, Flinke Pinke and Loco are all various incarnations of the same basic game. Colossal Arena is a card game where creatures battle to the death and was previously published as Titan: The Arena. In one of the stranger re-theming of a game, it was originally published in Germany as Grand National Derby, based around the famous horse race in England. Knizia explains, "The mechanics were relatively simple and it worked very nicely. It is a steeplechase and a lot of horses do not finish and drop out during the different hurdles. Then when the idea came from the American publisher to do a Titan: the Arena game we needed to beef it up a little bit. So more thematic elements came in and that brought a bigger range of different abilities for the cards, which the original horses didn't have. So we have a game that was very much liked in both markets with very different themes. Another example is my game Through the Desert, which is now a game of moving caravans. The working title of my original design was Rockefeller. The original idea was an island filled with rich people each trying to out-do each other by building the biggest palace and the biggest golf course and linked to the nicest areas of the island. These became oasis and palm trees and caravans of camels. This theme was actually suggested by the publisher because they thought they could position it better. They were right as the game has done well in many different languages."

When a game is re-published Knizia admits he is rarely picking up the game again in such an intense way. It usually works one of two ways. He leaves the game as is, perhaps making changes in the wording of the rules, but not the rules themselves. In other cases, he uses the opportunity to significantly change the game, so it is almost a new game. Knizia says, "Sometimes a different market requires something else like we did with Shotten Totten which became Battle Line that had extra cards that were not in the basic game. The extra cards make it thematically richer, which I think is the right thing for the American market."

Knizia thinks that electronics will become part of the future of boardgames. He points out that electronics are everywhere, in all sorts of products we use and we aren't aware of them because we don't have to think about them. In games there has been a separation between the social boardgames and electronic games. The electronic games are played in front of a screen while boardgames are more social and you played around a table with other people. With new technology, this is changing and he thinks the challenge now is to integrate the electronics into the game in a way that the player doesn't have to learn to operate these electronics, it simply happens. Knizia designed one of the most innovative electronic games to date with the King Arthur game, published in Germany by Ravensburger in 2003. Knizia says the real innovation of the game is not in the electronics, but in the board, which was produced with conductive ink. "That's where the magic starts. Players sit around the table and play it as usual, moving their figures around the board, but each figure has a chip and when the figure is placed on a space, through the conductive ink, the chip communicates with the unit without the player doing anything. So the unit knows who that player is and where they are and what they are doing. That enables the electronics to react so that players meet different characters and face different challenges. It brings up a totally new and enriched game atmosphere. The electronics really support and drives along the game without the player having to do anything. That's how electronics will be accepted into social games, as a supporting and enriching factor, and we will see many more of these games in the future." Unfortunately for game fans stateside, the game speaks and there's no English version available at this point.

Sometimes a game that is very simple on the face of it has a certain "x-factor," a secret ingredient of fun that materializes. Games like Trendy, Exxtra and Honeybears are good examples of simple games by Knizia that have this quality. Is this something that can be consciously designed? "I think that is something that I strive for," says Knizia, "You can recognize it in play testing, but not something that you can plan for. Through intensive testing I want to get this sub-conscious element that grabs the people. They don't know why it grabs them and they don't need to know. I'm the designer. I need to put that in and they can just enjoy it. But there are certain elements of the game that click with people. That's the right mechanic. Another one works as well but this is the mechanic that grabs the people, that stimulates them and encourages them to open themselves. This comes through a lot of testing and good luck as well. But it is something to watch out for and to bring a game to the situation where people say 'I don't know what it is about it, but this is a game I like.' Of course this is a rare process. It is very difficult to get there, but with all the testing that's where I'm trying to drive my games."

As anyone who has tried their hand at game design knows, a simple and elegant game is often the most difficult to achieve. So which is easier for Knizia to design? "A complex game that plays very long and has a lot of aspects integrated into it needs a lot of testing and is quite a challenge to do. A smaller card game is in this respect simpler to do, so I think in this respect complexity requires more work. If I have a big game, I want to make this game really round, taking off the corners and so it is intuitive to play and, perhaps unconsciously, very addictive. I think making a well-rounded game is always difficult and that can be for a small card game or a children's game as well as a bigger game. How many rough corners are there in the individual categories? Fixing that's quite hard to do. Making an 80% game is very easy. A lot of games that are out there are just 80% finished. With more testing the game could be more elegant and the last 20% takes a lot of time. That's the difficult part."

Knizia has never self-published and has strong opinions on the subject. "Everyone has their strengths and weaknesses and I think that designing games and publishing games are two very different occupations." Knizia says. "I have a limited number of hours in the day and in my life and I want to do the things I can do best. If I started self-publishing, that means I would have to get into the production and then the selling and distributing of the games. It requires very different experience and it is a totally different business. I want to stay in the game design business and not go into the publishing business. If I say yes to something else then I have to say no to game designing, at least to a certain degree, and I don't want to do that. I think it's a very naive thing to say 'Now that I've designed a game I think I'll self-publish it.' I might as well become a book publisher or produce music CDs. That seems odd, but simply saying about a game 'that's the same product, so I can do that.' Well no, I can't, and I won't. The desperation of some people saying 'no one will publish my game so I'll do it' is, in my eyes, a very dangerous temptation.

A detailed discussion of Knizia's prolific output could fill a book, but I couldn't resist asking about a recent favorite of mine, and a game that is rather unusual for a Knizia design, Ingenious. About the game, Knizia says, "It is now out in 12 or 13 different languages and still growing in the market. It was agreed up front that we wanted to do a more abstract game and see if we can bring out the fascinations through the tactical and tactile fascination with the pieces and what is created with simple game play and an exciting scoring mechanism. I was very fascinated to do that because abstract games can be difficult to play and it is usually a risk to develop. It was relatively straightforward. I never ran into any real big problems. There was a lot of testing, of course. I think it turned out very well and a lot of people mention it to me. There will be a CD ROM version coming out soon that will have tweaks and extra challenges."

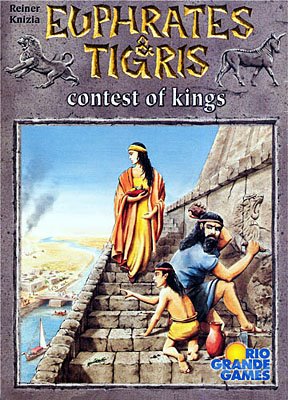

Another favorite is Tigris & Euphrates, one of the most original and challenging games available. I was very intrigued to hear that a card game version was planned, and was quite impressed when I had the chance to try it at the game fair in Essen, Germany. About the game, Knizia says, "It is called the Euphrat & Tigris card game for a reason because the core elements of Euphrat & Tigris are in there as well. You don't have to know the board game, but what you have the four different colors, the king, the trader, the priest and the farmer and you have the leaders again so you are building kingdoms but with cards and no board. It isn't a two-dimensional way but more a one-dimensional way where the kingdoms are columns and you play the cards in the columns. I wanted to make it very simple so you don't have any scoring cubes. Whenever you make a red point or a green point you have to play these points as cards from your hand. So if you make a green point and don't have any more green cards you don't get any points. There's a different component to it. It is not only that you want to play the right cards into the kingdoms but you also want to keep the right cards to score your points with. So it's much simpler than the board game but the basic elements are there. You have the kingdoms, you have the leaders, and only one color of leader can be in a kingdom. You have internal conflicts, which are still done on the red colors, and you have external conflicts when you join together two columns of kingdoms and they are fought out with card colors of the conflicting leaders. There are treasures; every kingdom has a treasure, so when you combine two kingdoms the trader can take the treasure. The game ends when all the cards are played or all the treasures except two are taken. So the basic elements are there but the entire approach is a true card game and therefore simpler and much shorter to play than the board game."

Another favorite is Tigris & Euphrates, one of the most original and challenging games available. I was very intrigued to hear that a card game version was planned, and was quite impressed when I had the chance to try it at the game fair in Essen, Germany. About the game, Knizia says, "It is called the Euphrat & Tigris card game for a reason because the core elements of Euphrat & Tigris are in there as well. You don't have to know the board game, but what you have the four different colors, the king, the trader, the priest and the farmer and you have the leaders again so you are building kingdoms but with cards and no board. It isn't a two-dimensional way but more a one-dimensional way where the kingdoms are columns and you play the cards in the columns. I wanted to make it very simple so you don't have any scoring cubes. Whenever you make a red point or a green point you have to play these points as cards from your hand. So if you make a green point and don't have any more green cards you don't get any points. There's a different component to it. It is not only that you want to play the right cards into the kingdoms but you also want to keep the right cards to score your points with. So it's much simpler than the board game but the basic elements are there. You have the kingdoms, you have the leaders, and only one color of leader can be in a kingdom. You have internal conflicts, which are still done on the red colors, and you have external conflicts when you join together two columns of kingdoms and they are fought out with card colors of the conflicting leaders. There are treasures; every kingdom has a treasure, so when you combine two kingdoms the trader can take the treasure. The game ends when all the cards are played or all the treasures except two are taken. So the basic elements are there but the entire approach is a true card game and therefore simpler and much shorter to play than the board game."With so many published games, what is Knizia's favorite? "There's no one game that I can say this is my absolute favorite game. It depends very much with whom I play. With different players I play very different games. It's a different atmosphere, a different mood. The history of what we've played before comes into the new game. There is no absolute favorite game. But, having said that, I'm hardly playing any of my published games. I'm usually playing my unpublished prototypes because there are so many on the go and in this respect always the new games I'm working on are my favorite games. Whenever there's an opportunity to play again, I can't wait to play these new designs and drive them forward and see how they develop. So my favorite game changes all the time."

It would seem that one could get jaded after having so many games published. But Knizia says it is still exciting when the published version arrives. "There are some games I particularly look forward to because I have a lot of effort going into it." explains Knizia, "For example King Arthur or The Island game because of all the electronics. We are no longer playing from our imagination but are playing the real thing, or the Blue Moon world with all the fascinating graphics. Of course getting your first game or book published is something special and I don't think you can really repeat that, but it is still great seeing the final product and it makes me very proud."

The Finer Reiner

A half-dozen Reiner Knizia games that should be welcomed into any game collection.

Tigris & Euphrates, Euphrat & Tigris Card Game

Tigris & Euphrates, published in the US by Mayfair, is one of my top five favorite boardgames of all time. This is an extremely interesting and challenging tile-laying game that gives players plenty to consider. The Euphrat & Tigris Card Game, just released here by Rio Grande Games (using the original German title), really captures the feel of the boardgame but is more streamlined and plays in less than half the time.

Winner's Circle

This is a rock-solid horse racing and wagering game, which is my favorite of the genre. Very well balanced, with a nice mix of luck and skill. Always a fun ride. It was released in Germany as Royal Turf in 2001 and the new version in English should be finally available from Face2Face Games.

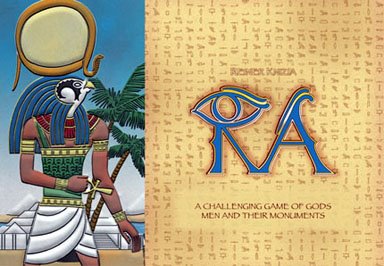

Ra

A wonderful auction game set in Egypt. Unavailable for years and going for over $100 on ebay, it has been reprinted by überplay in a new edition that features the original art by Franz Vohwinkel.

Lost Cities

This is a great two-player game, available from Rio Grande Games. It's sort of a competitive solitaire but with lots of game tension (that's a good thing, really!). An especially good game for couples.

Ingenious

This is a wonderful abstract game that is easy to learn but has lots of interesting decisions. My favorite version is the 4-player partnership.

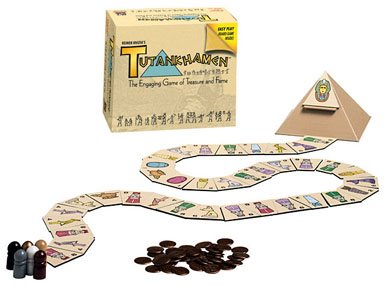

Tutankhamen

This is a very original set-collection game where all the information is public. Players travel along a path of artifacts, wanting to have the most or second-most when the last artifact is collected. Released in the US in a very nice, compact and affordable version from Out of the Box Publishing.

Author's note: An abbreviated version of this article was originally published in Knucklebones magazine #2 in January 2006. When I was assigned to interview Dr. Knizia it was for a 2,000 word article. I ended up with more material than they had space for, and they were able to stretch it to 2,500 words or so. This is the first time the full 4,000-word article has appeared.

Ward Batty is a long-time game-player who has been with the same weekly game group for over twenty years. "I understood there was a pension." is his excuse. He writes a monthly column on the business of board games for Comics & Game Retailer magazine and has written articles and reviews for The Games Journal, Scrye, Knucklebones and Games International.

The Game Table is a weekly column which is self-syndicated by the author. If you would like to see this column in your local newspaper, please write the managing editor of the paper. Interested in carrying The Game Table in your paper, please contact Ward Batty.